Romanian Version

Author: Lokodi Csaba Zsolt, Grafics: Anca Giura, Lector: Cristian Stefanescu

Translation: Daroczi Eniko

Short History of the Airedale Terrier

Standard Interpretation

Airedale Terrier Grooming

Whenever this breed is mentioned, the first words to come into one’s mind are invariably the same: ”it is the largest of the terrier breeds and it is known as the King of the Terriers”. We ourselves agree with this appreciation not merely because Airedales are the biggest of all terriers but mainly because of the various and fantastic qualities of the breed.

With their bright expression and brave attitude, Airedale Terriers are probably the most versatile of all terriers as they are used in hunting both fur and feather, and in retrieving on the ground as well as in water. Formerly, they were also put into action as ’gladiators’, earth dogs, watch dogs, police dogs and guide dogs for the blind. During the first world war they fulfilled missions as sentry dogs and courriers. There is no further need to say that a dog with a vast package of abilities like the Airedale excels even today in whatever activity it gets involved in. It is especially appreciated for its courage, for its sporting and hunting qualities, and last but not least for its infinite patience towards children. Throughout history, Airedale Terriers have proven endurance in extreme environmemtal circumstances from the icy lands of Canada to the deserts of Africa and Australia.

Short History

The breed originates from the valley of the River Aire, West Ridin, Yorkshire. People here were mostly miners and textile workers whose main free time activity was hunting along the river. The Airedale Terrier’s exact date of birth is unknown but there are several signs to indicate that the development of the breed started in the middle of the 19th century as a response to the locals’ desire to hunt otters. In those times a pack of Otterhounds and one or two Terriers were needed to hunt this aquatic water animal. In order to make their dogs work more efficiently and suited to water, the first amateur breeders did several interbreedings till a rustic-looking Airedale came out. There is plenty of written evidence to these cross-breedings, Old Black and Tan Terriers, Scottish Terriers, Welsh Foxhounds, Otterhounds, Bull Terriers, Collies, Dandie Dinmonds, Bedlington Terriers, Irish Terriers and hounds from the south of England are the most frequently mentioned ones. The first crossing between an Otterhound and an Old English Black and Tan Terrier is attributed to Wilfred Holmes who performed this achievement near Bradford in 1853. According to other versions, Border collies or other shepherd breeds were also used. Throughout times, lots of opinions have been published regarding the exact origin of the breed. One of the oldest and apparently the precisest one belongs to Vero Shaw who, in his book written in 1879, evokes the discussions with the owner of the dog Thunder.

”This breed was originally bred from a cross between one of the old rough-coated Scotch Terriers and Bull-terrier. What I mean by the old Scotch Terrier is a dog weighing from 12 Ibs. to 22 Ibs., with a bluish-grey back and tanned legs, with a very hard and coarse coat. This cross, of course, did not produce a large dog, neither had the animal a very keen nose, so it was then crossed with Otter-hound, thus producing a large, ungainly animal, with big ' falling ' ears, and very soft coat. This was then crossed and re-crossed, first with the original cross, and then with Bull-terrier, to produce a good terrier ear and good feet.This again was crossed with Otter-hound, the offspring not showing so much hound, neither having such a soft coat, but possessing a good nose for hunting, and a fondness for water as well as great gameness, both from the Bull blood as well as from the hound.

Then this was crossed with Bull again, and then the offspring crossed and re-crossed with the terrier till it was brought up to the present standard.”

The interest towards the new breed rapidly increased, especially in Yorkshire where the dog acquired different local denominations: Bingley, Otley or Waterside Terrier.

From now on the new breed gained a particular popularity due to the audacity with which it dominated any adversary. The new dogs got used to the sound of gunfire and they were trained to retrieve. They were fierce competitors at water rat huntings, a then popular game.

At these recreation events organized to entertain workers, several groups of terriers gathered and each dog had to catch as many rats as it could in a given period of time. Here is what Albert Payson Terhune said on the game:

”Among the mine-pits of the Ayr, the various groups of miners each sought to develop a dog which could outfight and outhunt and out-think the other mines’ dogs. Tests of the first-named virtue were made in intermine dogfights. Bit by bit, thus an active, strong, heroic, compactly graceful and clever dog evolved – the earliest true form of airedale. (…) Out of the experiments emerged the modern airedale, a dog that does not know the word ’fear’.

He is swift, formidable, graceful, big of brain, and there is almost nothing he cannot be taught if his trainer has the slightest gift for teaching. (…) Every inch of him is in use … No flabby by-products. A perfect machine – a machine with brain, plus.”

A largely successful re-union of Airedale-lovers and breeders was Scarborough Centenary Exhibition in 1976, even if nobody knew for sure whether the breed was 100 years old or not. Breeders from all over the world met on this occasion.

In the summer of 1997, the Airedale Terrier Breed Council was assembled to scheme the project for the breed’s greatest festival to be held in 2000: the Airedale Terrier Millenium Celebration, or the Airedale’s come-back to Bingley.

As for the first attestments, at an 1860 exhibition there was only one section for wirehaired terriers. The dogs participating here are believed to be the old Airedale Terriers. At the 1876 exhibition of Shipley the breed was represented by a stock of as many as 58 dogs with homogenous characteristics, forming a separate section. Three years later, in 1879, judge Gordon Stadles, an enthusiast of the breed uses the denomination Airedale Terrier for the first time. At first, the name came in usage in exhibitions at the sections destinated especially for the breed. In 1885, the Kennel Club recognized Airedale Terriers as a separate breed.

The first attestments in the Birmingham National Dog Archives date back to 1883, and then, three years later AT can also be found in the studbooks of the Kennel Club, in a breed class of its own.

The first breed standard was elaborated in 1892, based on the exhibition files of Ch. Cholmondely Briar, the first Airedale winner of the Challenge Certificate.

During the decades that followed the breed was brought to perfection by diminshing the hound characteristics.

Until 1911, AT was designated as a police dog for patrol purposes, and as soon as the first world war broke out, Airedales were charged with their greatest mission ever: they became messengers, sentries and ambulance dogs on the Western front.

In 1919 National Geographic describes AT as ”the most popular terrier in the United States”, and praises its courage, loyalty and confidence. It is the magazine that gives its weight as well: from 35 to 45 lbs. The same article written in 1936 draws the attention to the Airedale because of the courage it works with even in extreme temperatures.

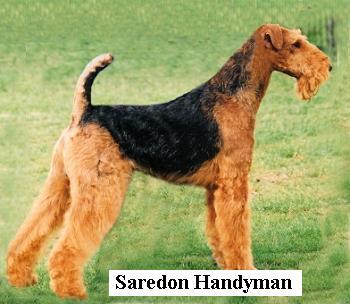

From 1945 on, AT has excelled in show rings, winning twice at Crufts in England.Below are some dogs from England contributing to the evolution of the breed from 1945 on. Their names can be found worldwide, in all blood lines.

Airedale Terrier Standard & Interpretation

In its form published on 13./10./2010 – approved as compulsory by the FCI – the breed standard gives a brief, concise and comprehensive description of Airdale Terriers. The standard is measure and purpose for both breeder and judge. For a better understanding, a detailed explanation is required, providing with full information on each point, if necessary. This supposes a profound knowledge of anatomy.

Corporal regions:

1 – nose; 2 – muzzle/foreface; 3 – stop; 4 – eye; 5 – skull; 6 – ears; 7 – lips; 8 – cheek; 9 – neck; 10 – withers; 11 – back; 12 – loin; 13 – chest; 13a – forechest; 13b – brisket; 14 – flank; 15 – abdomen; 16 – tail; 17 – point of shoulder; 18 – shoulder; 19 – upper arm; 20 – elbow; 21 – forearm; 22 – knee; 23 – front pastern; 24 – paw; 25 – croup; 26 – point of buttock; 27 – thigh; 28 – stiffle; 29 – gaskin/second thigh; 30 – hock; 31 – rear pastern.

Skeletal system:

1 – maxilla; 2 – mandible; 3 – cranium; 4 – cervical vertebra (7 in number, the first one being the atlas); 5 – thoracic vertebrae (13 in number); 6 – lumbar vertebrae (7 in number); 7 – sacrum; 8 – caudal vertebrae (20-22 in number); 9 – scapula; 10 – humerus; 11 – radius; 12 – ulna; 13 – carpal bones (2x7); 14 – metacarpus; 15 – phalanges (4x3+1x2 front, 4x3 rear); 16 – sternum; 17 – costae (9 pairs connected and 4 pairs not connected with the sternum); 18 – coxal/pelvis; 19 – femor; 20 – patella; 21 – tibia; 22 – fibula; 23 – tarsus; 24 – calcaneus; 25 – metatarsus.

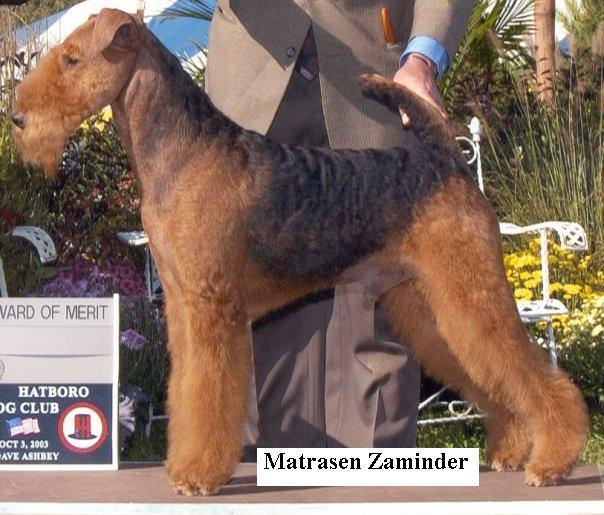

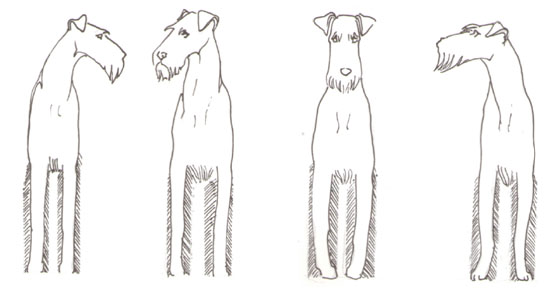

“GENERAL APPEARANCE: Largest of the Terriers, a muscular, active, fairly cobby dog, without suspicion of legginess or undue length of body. “

As for its outlook, the AT’s most distinctive feature is symmetry, which means that none of its morphological characteristics should be too obvious. Its outer aspect, as well as its temperament should convince by symmetry, harmony and balance. Exaggerating certain points of the Standard would depreciate the qualities of the specimen.

Its body in profile forms a square, with the distance between its chest to the edge of its backsite equaling its height at the shoulders. The chest should reach the level of the elbows, dividing the height from the withers into two equal parts.

“BEHAVIOUR AND TEMPERAMENT: Keen of expression, quick of movement, on the tiptoe of expectation at any movement. Character denoted and shown by expression of eyes, and by carriage of ears and erect tail. Outgoing and confident, friendly, courageous and intelligent. Alert at all times, not aggressive but fearless.”

Thus, according to the Standard, there are two features absolutely undesirable with this breed: agression and fear. An Airedale is an extremely adaptable dog, with an irresistible and playful temperament, with a proud and confident attitude. It is very patient with children, and when excessively annoyed, it rather keeps distance than doing any harm. It is endowed with a strong will but is tender and affected to its family. It is very inquisitive, loyal and intelligent, alert and always ready to play. As for its hunting abilities, the same Vero Shaw eloquently notes in his description written in 1881: ”Airedale Terriers can kill anything, and will do anything. They can be broken to the gun, and broken to ferrets; they can go out ratting and they will not touch a rat in the net, they will drive sheep and cattle like a Sheep-dog, fetch and carry like a Retriever, hunt like a Spaniel and are as fond of water as a duck, and as game and obedient.” US President Theodor Roosevelt, who hunted with an Airedale for many years, also praised the breed: "An Airedale can do anything any other dog can do, and then whip the other dog if he has to".

“HEAD: Well balanced, with no apparent difference in length between skull and foreface. Free from wrinkles.

CRANIAL REGION:

Skull: Long and flat, not too broad between ears and narrowing slightly to eyes.

Stop: Hardly visible.

FACIAL REGION:

Nose: Black.

Muzzle: Foreface well filled up before eyes, not dish-faced or falling away quickly below eyes, but a delicate chiselling prevents appearance of wedginess or plainness.

Lips: Tight.

Jaws / Teeth: Upper and lower jaws deep, powerful, strong and muscular, as strength of foreface is greatly desired. No excess development in the jaws to give a rounded or bulging appearance to the cheeks. Teeth strong. Scissor bite, i.e. upper teeth closely overlapping lower teeth and set square to the jaws preferable, but vice-like bite acceptable. An overshot or undershot mouth undesirable.

Cheeks: Level and free from fullness. “Cheekiness” is undesired.

Eyes: Dark in colour, relatively small, not prominent, full of terrier expression, keenness and intelligence. Light or bold eye highly undesirable.

Ears: « V »-shaped with a side carriage, small but not out of proportion to size of dog. Top line of folded ear slightly above level of skull. Pendulous ears or ears set too high undesirable. “

The head is long, well-proportioned, being approximately 42% of the height measured from the top, while the longish and flat skull has to be as long as the muzzle/foreface. That is, the length of the head (from the nose to the occiput) is divided into two equal parts by the imaginary line between the inner eyes commissure. Viewed sideways, the cranial topline and the nose level should be parallel and then meet in an almost straight line, with a stop hardly visible.

The head is long, well-proportioned, being approximately 42% of the height measured from the top, while the longish and flat skull has to be as long as the muzzle/foreface. That is, the length of the head (from the nose to the occiput) is divided into two equal parts by the imaginary line between the inner eyes commissure. Viewed sideways, the cranial topline and the nose level should be parallel and then meet in an almost straight line, with a stop hardly visible.

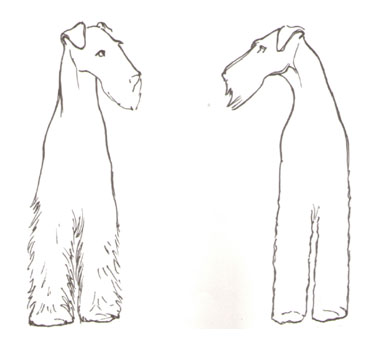

The skull should be free from wrinkles, that is lean and lanky, without any surplus skin. When the dog is attentive, this defect becomes at once obvious and wrinkles appear. The skull itself is narrow between the ears and gets slightly narrower to the eyes. A too narrow skull creates the impression of weakness, or in case of a male the impression of a female. On the other hand, a broad, stern and heavy skull gives the feeling that the dog lacks intelligence.

The cheeks are smooth and flat, without any fullness. The foreface should be strong and well filled, but ifslightly chiselled, it improves the expression of the face. The quality of the grooming plays an important role in highlighting the correct type. Jaws should be strong and muscular. The teeth, strong and well-developed, should close in a scissors bite, i.e. the upper incisors and the lower ones superpose with no space between. Preferably, their insertion should be perpendicular on the jaws, however, a vice-like bite is also acceptable. In order to preserve the desired – that is, a broad and powerful – foreface, it is important to pay attention to the dentition, thati is the proper setting of the incisors in a straight line.

The lips should be tight, pigmented black if possible. The nose should be big, broad and black A delicate, tender nose always indicates a subtle foreface which even hair will not attenuate.

The eyes should be small, oval-shaped, not prominent, with a watchful and intelligent expression and of a colour as dark as possible. Light-coloured eyes represent a serious defect, which can be eliminated only with difficulty, and it modifies the typical terrier expression. Eyes too big and round will also modify the expression as they suggest a kind and an overfriendly look. Almond-shaped, narrow eyes resembling that of Bull Terriers’ should be avoided in selections because they, too, alter the general aspect; the gaze will thus become far too vicious.

The V-shaped ears with a side carriage should be small, proportional to the dog’s size. The topline of the folded ear is slightly above the level of the skull, while the tip of the ear reaches the outer edge of the eye level. Ears positioned too low and set laterally – as with hunting dogs –, or too high on the skull and pointing to the eyes – as with Foxterriers – are not accepted. The inner part of the ears should be clinging to the temples.

“NECK: Clean, muscular, of moderate length and thickness, gradually widening towards shoulders, and free from throatiness.”

“NECK: Clean, muscular, of moderate length and thickness, gradually widening towards shoulders, and free from throatiness.”

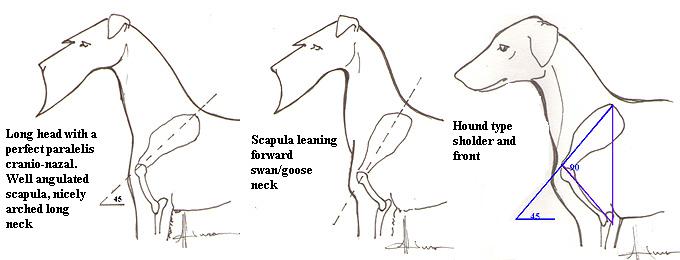

The neck – formed of the seven cervical vertebra – is muscular and lean, slightly resembling the shape of a truncated cone.

The topline of the neck in side view describes a lightly bended arch to meet the well-marked withers in a smooth and elegant upper line. A dewlap is undesirable as it distorts the lower line of the neck which should be lean. The insertion is of about 45º.

Too deep or too abrupt insertions (ewe neck) are undesirable.

“BODY:

Back: Short, strong, straight and level, showing no slackness.

Loin: Muscular. In short-coupled and well ribbed-up dogs there is little space between ribs and hips. When dog is long in couplings some slackness will be shown here.

Chest: Deep (i.e. approximately level with the elbows) but not broad. Ribs well sprung.”

The body of an Airedale is a perfect square. The well-framed, distinct withers (formed of the spinal apophyses of the first 4 or 5 thoracic vertebrae) harmoniously joins to the strong and straight back (containing the next items of the thoracic vertebrae) and to the short (of 7 lumbar vertebrae), strong, very muscular loins. With a dog with well-arched (but never rounded, barrelled-shaped) ribs, short loins and a rather muscular posterior train, there always remains some space between the last rib and the thigh.

With a specimen like this, the coupling is short, while the top-line is harmoniously profiled from the nape to the base of the tail. If the lumbar zone and the back is too long, a certain weakness of the body appears. The back should never be either saddled (concave) or arched (convex). In motion, the back should be level, straight and strong, with neither curves nor deviations due to weakness.

The chest is made up of 13 pairs of ribs, the first nine pairs being connected, the next four ones not being connected with the sternum (sternal and asternal ribs). The chest should reach the point of the elbow in order to ensure good and endurant movement. The well arched costae have an important role in offering enough room for the heart and lungs. The pro-sternum is slightly visible in front of the shoulder blade. The abdomen is hollow and loose, the lower line having a slight bending.

“TAIL: Previously customarily docked.

Docked: Set on high and carried gaily, not curled over back. Good strength and substance. Tip approximately at same height as top of skull.

Undocked: Set on high and carried gaily. Not curled over back. Good strength and substance.”

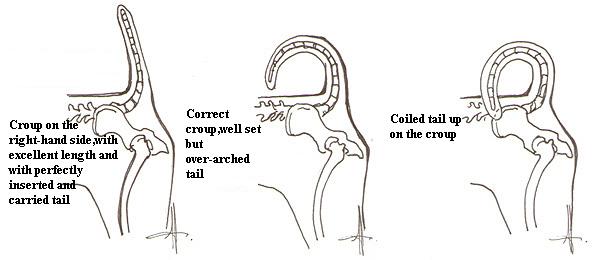

Prior to tails we can’t help talking about the croup formed of the three sacrum and the upper part of the pelvic girdle. The croup should be short and level.

Any turning off, such as a drooping, round croup, a too long or too short one, distorts the characteristic harmony and symmetry as they are consequences of functional defections. Defects of the croup are related to defects of tail carriage and of posterior angulations as well.

The tail is strong, of moderate thickness. With docked tails (that is at about 2/3 remaining) the tip should be at the highest point of the skull level.

Rolled-up, curly tails set on the back or on the flank is unaesthetic and spoils the dog’s harmony and functionality.

A low-set tail carried as an extension of the croup will make the top-line longer and alters the movement of the dog.

An undocked tail will never be as straight as a stick or perpendicular to the croup; but it perpendicularly starts from the croup, then at halfway it slightly curves to the head, parallel with the neck.

“FOREQUARTERS:

Shoulder: Long, well laid back, sloping obliquely. Shoulder-blades flat.

Elbow: Perpendicular to body, working free of sides.

Forearm: Forelegs perfectly straight, with good bone.

Forefeet: Small, round and compact, with a good depth of pad, well cushioned, and toes moderately arched, turning neither in nor out.”

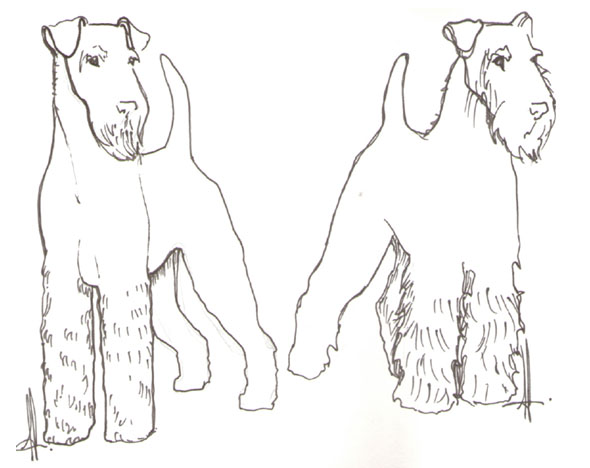

Viewed from the front, the forelimbs should draw an absolutely parallel line from the elbows to the toes.

Deviations of the elbows or of the paws inward (cagneux) or outward (panard) make serious defects, as well as a too narrow or too broad chest.

The scapula should well oriented backwards, it should be long, level, obliquely set at about 45º. It should be musculous but level; a globular musculature is totally undesired.

![othello%20kirm[1]](/images/stories/othello%2520kirm%5B1%5D.JPG)

In my opinion this concept is not right for terriers, especially because this way the distance to the centre of gravity will be lessened. Thus, the angulation may be even larger and the upper arm slightly shorter, so that the perpendicular from the highest point of the withers to the ground (the line where the centre of gravity is as well) is lightly behind the elbow, and the point of shoulder somewhat behind the fore-chest. The length of the pace will be given by the mobility of the scapula helped by the musculature of scapula and neck. Such a shoulder with a narrow front and hindlimbs with a proper distance between them help Airedales in quick turning.

The scapula, together with the apophyses of the first thoracic vertebrae, should induce oblique, long withers.

The elbow, dividing into two halves the height at the withers, is perpendicular to the body and moves freely near the chest with no deviation in or out. The forearm should have a strong skeletal system, it should be straight and substantial.

The paws are small, rounded and compact (catpaws), with well-developed, black pads. The moderately arched phalanges with black toes have deviations neither in nor out.

“HINDQUARTERS:

Thigh: Long and powerful.

Stifle (Knee): Well bent, turned neither in nor out.

Lower thigh: Muscular.

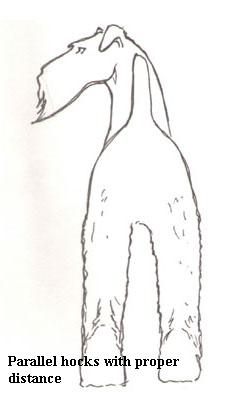

Metatarsus (Rear pastern): Hocks well let down, parallel with each other when viewed from behind.

Hind feet: Small, round and compact, with a good depth of pad, well cushioned, and toes moderately arched, turning neither in nor out. “

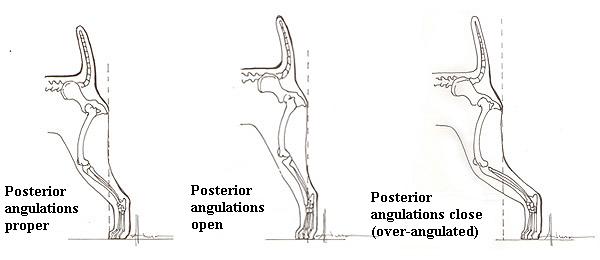

Hindquarters make up the propulsive mechanism. Thigh and gaskin should be long and very muscular. The knee joint should be strong, well-bent (the angulation is about 160 - 165º). The point of buttock should be visible but not too prominent – it is more rounded than with Foxterrieres.

The rear pastern is perpendicular to the ground, with hocks close to the ground and making

perfect parallels when viewed from behind.

Any deviation in or out (knock-knees or bow-legs) significantly diminishes the propulsion of the hindlimbs.

Posterior angulations are proper when an imaginary perpendicular drawn through the point of buttock to the ground is right in front of the rear paws.

Paws in the front and in the rear are similar.

“GAIT / MOVEMENT: Legs carried straight forward. Forelegs move freely, parallel to the sides. When approaching, forelegs should form a continuation of the straight line of the front, feet being same distance apart as elbows.

Propulsive power is furnished by hindlegs.”

When moving, the dog should cover distances with no effort.

The forequarters move forward with long and deep steps. Viewed from the front, forelegs should be absolutely parallel and working free near the sides; they should be on the same line with the front. Elbows and feet should be at the same distance. Crossed limbs with distant elbows (loose shoulder) or elbows gathered under the chest, with limbs spread outwards (tight shoulder) are undesired. Similarly, there is another movement that sometimes can be observed with the forelegs: legs raised too high and put back on the ground almost on the same place (typical for Hackney horses). Thus, the loss of energy will be very great and the length of pace very reduced. The length of step is adequate when the forelimbs move the forequarters deeply forward, about at the same oblique line with the scapula.

move the forequarters deeply forward, about at the same oblique line with the scapula.

The propulsion comes from the appropiately muscular hindlimbs with a long gaskin; viewed from the back they should be perfectly parallel, at a distance approximately equal to the height of the hock measured from the ground. In case of right movement the pads of the hindlegs can be seen. Any attempt to raise the metatarsus higher is undesired and will produce loss of energy. If we observe the movement of an Airedale in snow or wet sand, the traces should form a single line, the hindlegs stepping where the forelegs formerly have.

The motion should be an elastic one, well-balanced, covering much area and showing surety, pride and attention. Movement is what indicates good anatomy, and represents an important point of view in judging.

“COAT:

Hair: Hard, dense and wiry, not so long as to appear ragged. Lying straight and close, covering body and legs; outer coat hard, wiry and stiff, undercoat shorter and softer. Hardest coats are crinkling or just slightly waved; curly or soft coat highly undesirable.

Colour: Body saddle black or grizzle as is top of the neck and top surface of tail. All other parts tan. Ears often a darker tan, and shading may occur round neck and side of skull. A few white hairs between forelegs acceptable.”

Dogs with a robe of a hard texture have less hair on their feet and beard which means an advantage for utility dogs, but Airedale breeders consider it less aesthetic. Soft and abundant hair on the legs and on the muzzle are defections. It can hardly be stripped and taken care of. Such hair usually is dull and of a lighter colour, tending to beige. It tangles much sooner and gets dirty.

The hair on the back of the head, on the back and saddle, as well as on the upper part of the tail is black or grizzle. All other zones of the body are tan.

.jpg)

Grizzle is a uniform colour, a blend of grey, black, white and copper-coloured hairs, similar to what is called hoary. Tan is a colour of a golden-brownish tone, resembling autumn leaves.

Ears often have a lighter tint of tan; lighter shadows might appear round the neck and also on both sides of the skull (on the temples).

A slight blending of colours on the shoulders and on the thigh should not be considered defect, although it unfavourably modifies the proportions. At birth the puppies are black (very much similar to Doberman ones), with few marks of tan, in the course of time, the change of colour will gradually take place. If after age 2 the dog has black shoulders or thighs, will keep them all life long. The so-called soft ‘Aphgan-hair’ usually is greyish, cream-coloured on the head and limbs. The greyish colour often remains on the ears and on the external sides of the skull. Such dogs, called ‘woolies’, are anatomically well-built but have undesired hair. This type of hair is an eliminatory defect.

Some white hair between the forelegs is accepted but white paws with rosy-coloured nails and toes constitute a serious defect.

“SIZE AND WEIGHT:

Height at the withers: About 58 - 61 cms for males.

About 56 - 59 cms for females.”

The size of the males is preferably of 23-24” and 22-23” with females which approximately corresponds to the Standard data in centimetres.

Height is measured from the highest point of the withers, directly next to the shoulders down to the ground. A dog with prominent withers might seem taller than one of the same size but showing washed-out, under-developed withers with an inadequate insertion of neck. A 58 cms male dog will appear a bit ‘feminine’, while the one much over 61 cms has a coarse and easeless aspect. The bitch should not measure less than 56 cms, or else type and quality will be spoilt. On the contrary, it may be almost as large as a male if the feminine aspect, gracefulness and harmony are kept. Compact dogs always seem smaller than the ones tall of legs, with insufficient thoracic depth and a longer back.

The quality and the general impression of the dog should always be a more important point of view than precise measurement!

“FAULTS:

Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare of the dog.

DISQUALIFYING FAULTS

• Aggressive or overly shy dogs.

• Any dog clearly showing physical or behavioural abnormalities shall be disqualified.

N.B: Male animals should have two apparently normal testicles fully descended into the scrotum.”

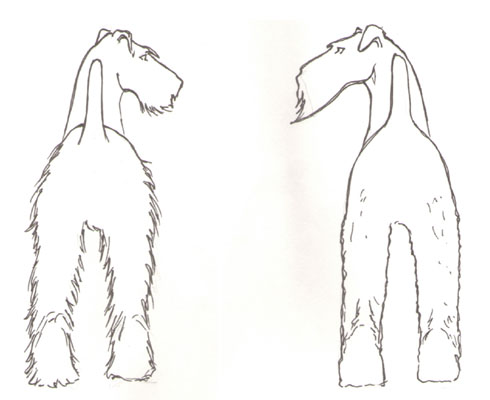

Airedale Terrier Grooming

Caring does not suppose much effort as the Airedale is a less pretentious dog which rarely becomes ill. With good alimentation and right grooming, the risk of illnesses at this breed considerably decreases. Airedales like other wire-hair terrier breeds, is mainly inclined to certain affections of the skin only if the hair is not adequately taken care of. They have rough, dense and rigid hair which does not shed the same way as with smooth- or long-hair breeds (more exactly, they do not leave hair everywhere around, but tufts of dead hair stay clung to the fur). If not properly taken care of – by pulling out hair from time to time – the coat will get clogged, it will not let the skin breathe which advances the appearance of dermatitis. As for hair caring, it does not only have aesthetic purposes but also strictly hygienic ones.

The operation itself is a laborious one and requires patience. Besides patience, we need of course suitable tools, first of all stripping knives.

Most breeders and professional handlers prefer working entirely with these knives, without using scissors or electric clippers hardly at all.

Stripping knives are made of different kinds of special steel, they have teeth of different size, sharpened in different angles (some only strip, others cut as well). In the hands of an expert, stripping knives become veritable chisels for hair sculpture where every single hair keeps where it belongs to, with fine transitions from one length to another – that would be the ideal image of a well-groomed Terrier.

Before starting we should define our aim: are we going to do the grooming for strictly hygienic purposes or for show. Certain stages are similar. Again, what matters a lot is the quality of the hair, from extremely wiry to extremely soft.

Extremely soft, woolly hair can be pulled out with difficulty and causes pain (the skin gets very irritated), rapidly tangles, it is difficult to take care of and is not characteristic of the breed. Unfortunately, the quality of the hair will not improve. If I had such a specimen, I would not take it to shows. Nevertheless, it needs grooming. I would comb it very, very thoroughly, undoing every tangled part, and I would choose a long and wide-tooth knife that does not cut at all.

With it, I would go deeply underneath the coat to take out the smooth and puffy hair, usually of silver-grey colour which is not hygienic as it blocks skin breathing and produces those smelly eczemas.

As a rule, this type of knife pulls out much of the dead hair, and some of the tectorial hair. I would not leave undone the legs as well.

Once the dog got rid of dead hair, it has to be trimmed short to a shape typical to the breed.

This process takes about 8 hours.

In case of specimen with good hair, the hair entangles less and with brushing a great majority of tows will disappear. This operation can be done with a specially designed grooming brush with a blade that removes the loose hair from the undercoat (for e.g. FURminator).

In case of specimen with good hair, the hair entangles less and with brushing a great majority of tows will disappear. This operation can be done with a specially designed grooming brush with a blade that removes the loose hair from the undercoat (for e.g. FURminator).

After a thorough and minute brushing, I choose a knife with long, wide and thin teeth which enables me to penetrate in the depth of the fur, then I begin to pluck out the hair. Plucking will always start from the head towards the tail, the same direction with the hair growth. It is very important the position of the knife in the hand. The thumb should be over the blade, we pull the knife onto the hair and with the thumb we fold the hair tight on the blade. Thus, the hair gets blocked into the teeth of the knife, and with a sudden and quick single movement of the wrist we pull. The other hand holds the skin stretched opposite to the plucking.

After having cleaned the back of the neck, we go on towards the tail plucking all existing hair. As a result, the skin will remain smooth and velvet-like. In most cases minor irritations will occur so we will have to apply some ointment to soothe and protect the skin. Such irritations usually do not last for more than 2 or 3 days. The dog must not be exposed to the sun during the first week not to get sunburn. In order to sanitate quality hair, the scapula zone will be cleaned off with a smaller tooth knife, then the area under the neck follows (downwards direction – at the point where black hair meets reddish one, a change of the growing direction can be observed). The cranial zone will be stripped then, up to the commisure of eyes and lips. Both parts of the tail follow, beginning with the root to the tip. Usually, a rougher kind of hair can be found here. Below the tail, in the area of the anus and genital organs one should work with great care as these are extremely sensitive zones. If the hair does not come out with ease, I make use of thinning shears, clippers or knives with smaller teeth and a thinner blade that is sharpened, most preferably a knife that cuts as it also takes out a part of the dead hair.

The zone of the anus is to be trimmed to skin, and this is where from I start doing a slight transition towards the gaskin. Thus, the transition begins from the upper part of the gaskin - where black hair meets tan colour – to the hocks (forming a triangle). From anus to hocks I pluck off everything. I do the transitions at the elbows, at the chest and thoroughly clean the hair between the paws. This way, we get a healthy fur in 8 weeks. Manual labour lasts for about 8 hours.

In case of grooming for show, at first I only pull out the part that has to grow longer, that is the black part. Starting from the back of the neck I go down to the neck zone till the two colours meet and the hair changes its direction of growth, then from here on to the withers, the sides of the chest to the tan colour, the lumbar zone and the upper part of the tail.

Even if such a grooming is not pleasing to the eyes (for a while, it even looks ridiculous), this is the only way to obtain hair of good quality and proper length for the show. This process starts 10-12 weeks before the shows scheduled.

I intensely comb the hair on the legs, on the chest and on the beard, getting rid of eventual dead hair. I presume there is rich and dense hair on the legs at this stage. If not, re-conditioning has to be started much, approximately 8 months earlier.

This is the period when I also work on the black zone in case the first hair is greyish and silky. We should bear in mind that the undercoat has to be shorter than the coat, otherwise the quality of the back zone hair will not be fit for show. There is no need to worry about plucking it out because – as it is usual – quality hair grows underneath, so the undercoat has plenty of time to grow under tectorial hair. The coat on the back should be strong with straight hairs or, in case of very strong hair, lightly wavy and glossy. White or reddish hairs of good quality mixed in the saddle do not represent any problem.

Although bibliography says that the shorter part should be stripped 2 weeks before the show, from my personal experience I can tell you that the process might be started even 4 weeks earlier. Thus, the hair has enough time to grow and allow corrections and gentle blendings as natural as possible.

For trimming the head the knife I choose depends on the length of hair; if the hair is at its natural length and has grown old I use a knife very similar to the one used at the back. I do the plucking the same way as I had with the santitation of the skin, that is at the skull I strip off everything so that the skin can be seen – at the arches (leaving hair for the eyebrows), up to the commissure of the eyes and under the chin up to the corner of the mouth. Then from the contact zone of the two colours I go down and pluck the area of the shoulders to the elbows, as well as the lower part of the of the neck, to the point of shoulders.

At the hindlimbs I apply the same method as with sanitation, except for that I do the plucking a lot more carefully so that later I can emphasize the point of buttock and the hocks.

I clean off the long hair from in between the toes, taking care not to produce holes as afterwards I have to round up the paws. Within the zone of the abdomen I take off only that much as not to give the impression of hollowness, plus to have enough hair to form the lower line. The hair on the ears preferably should be completely plucked off, but being an extremely sensitive area, I usually only pluck some part, and for the rest I use really short tooth knives with sharpened blade. In the inner part I pluck off as much as the dog lets me, and the remaining part is done with an electric clipper, blade size very small, even 0. At this stage I will also take off the the tan part from the whole length of the tail.

This way, in 4 weeks the reddish hair will homogenise with the black one. At least once a week I comb the legs and the muzzle; too much combing will break the hair and will lessen the volume. Hair should be taken out only as much as to avoid entangling, –there are specimen with undercoats denser than usual so a quicker tangling is likely to occur. Such dogs usually have more rich hair. The growing of the hair is influenced by the season, by the conditions the dog is kept (outside or inside the house), and by the alimentation.

Supposing the hair on the back has been growing for about 9 weeks, on the legs there is rich hair in perfect condition, the beard is long containing plenty of strong hair, and in the short zones hair has jus started to grow – then it is the right moment to begin finishing. In order to do it, we need a profound study of the specimen, and we need to compare it to the interpretation of the Standard. I always look at dog as a whole; I figure out how I would like it to look like, and in finishing I try to make it as similar as possible to the ideal.

I begin with the cranial zone. According to the Standard the head should be long with a flat skull, slightly narrowing to the nose. This feature can be highlighted by the length of the beard. So we should aim at a beard as long as possible, of a subtle form, a not too thick one, starting from below the eyes and narrowing to the nose. The line of nose should be parallel to the skull with a stop hardly noticeable. As too much hair on the cranial top-line does not look nice, it is advisable to obtain the desired parallelism using the hair on the nose line.

We mustn’t ever thin out the hair on the sides of the foreface; it would give the impression of too weak jaws. The beard line viewed from above should come as a continuation of the cheeks (which are flat), narrowing slightly to the nose. If we made these lines completely parallel, the head would seem too full under the eyes, too rough and unnaturally short. The muzzle should be strong and full, however, a light chiselling improves the dog’s expression. The lower profile of the beard should form a line as smooth and curved as possible, to be continued in the lower neck-line and down to the toes.

I always comb the beard in a forward direction, the upper sides downwards, slightly to the point of the beard. Under the eyes we need to do a light transition (be careful not to deepen too much), because we do not want the cheeks to seem washed out or hollow. The eyebrows should be triangle-shaped, from the outer eye commissure to the inner corner of the eyes. I never leave the eyebrows too bushy, I rather form them as an elongation of the skull. We need to obtain a fiery expression. Though, in case of big eyes we should tone down with plenty of hair. The eyebrows will be bigger, thicker and broader, but not as voluminous as with Schnauzers.

The ears should be shaped according to the head and the gait, of a darker shade of reddish, and of velvet-like texture. I always cut off larger ears with scissors, almost to the skin; in case of small ears we should leave some hair on the tips so that they seem bigger and more voluminous. I keep an eye on their top-line; they should be above the cranial line while the tips should form the shape of ’V’, reaching the commissure of the eyes.

Finally, if needed, I either leave or take off the hair from the cheeks and the sides of the skull, as too a narrow skull gives the impression of weakness, while a too broad one seems dull. The whole head should be in harmony with the body. I never leave any hair on the occiput, some say it makes the head longer, but in my opinion it lessens the distance between the ears’ top-line and the skull, and what is more ponderous, it makes the skull longer with detriment to the muzzle, thus the cranio-nazal correlation – which should be unifom – is lost.

From the occiput, the transition to the neck is a very gentle line, slightly curved to the withers. This line might be anatomically given, so we do not need to exaggerate it; in case it is not given, we can form it using hair, and similarly, strong, well-distinguished withers can be formed from hair, as well. Thus, the top-line (from the occiput to the root of the tail) is a continuous line, descending at the beginning, then after the withers (back and croup) becoming absolutely straight. If the top-line is not formed anatomically this way, we need to form it using the hair. For this purpose I recommend sharp knives and thinning shears to work on with; we will have to trim in the same direction the hair grows. Blendings should be made carefully; the hair should look as natural as possible. We may use quite sharp knives here, scissors, even electric clippers. We need to perform the operation a few days before the show, allowing the hair to get placed.

From the occiput, the transition to the neck is a very gentle line, slightly curved to the withers. This line might be anatomically given, so we do not need to exaggerate it; in case it is not given, we can form it using hair, and similarly, strong, well-distinguished withers can be formed from hair, as well. Thus, the top-line (from the occiput to the root of the tail) is a continuous line, descending at the beginning, then after the withers (back and croup) becoming absolutely straight. If the top-line is not formed anatomically this way, we need to form it using the hair. For this purpose I recommend sharp knives and thinning shears to work on with; we will have to trim in the same direction the hair grows. Blendings should be made carefully; the hair should look as natural as possible. We may use quite sharp knives here, scissors, even electric clippers. We need to perform the operation a few days before the show, allowing the hair to get placed.

I comb the forelimbs opposite the direction of growth in order to gain volume, then slightly downwards, forming a column. The elbow should be thinned to fit completely within the frames of the column, we might even lengthen the column above the elbow, especially with a dog with a deep chest. Thus, the legs are made longer and we create the impression of a more compact dog. Longer hairs will be pulled off with the finger. To do this, you can purchase latex finger cots, but you may also make good use of the tips of rubber gloves. I round off the paws with great care, trying to make them as compact as possible, and as hidden in the column as possible. According to the Standard, Airedales should have ’cat paws’.

It is extremely important to look at the forelimbs from the front; they should be absolutely parallel and on the same line with the shoulders.

We mustn’t ever deepen too much between the legs because we need a narrow and parallel front. If the paws are turned out (panard) or in (cagneux), the defect is preferably attenuated with hair, by shaping the paws: we leave more hair opposite the turning and less in the direction of the turning. This way we will get parallel columns.

After having finished with the forelimbs it is highly advisable to have the dog move so that we can see the impression the forelimbs give. In case it is neccessary, we can further do some touching up till the forelimbs viewed from the front and in motion appear parallel. Many tend to deepen at the level of the elbows, too, which gives the impession of weakness, the elbows seeming to be positioned much under the trunk.

This is the same zone where I have often noticed too much hair left on the forechest, which I think lengthens the dog and makes the forechest seem much too strong and loaded. Here we need to shape a smooth and uniform profile, from the beard down the toes, while the sternal point should remain clear and slightly visible.

With hindlimbs it is very important to follow the instructions of the Standard, that is:

long gaskins, hocks well let down and parallel. At the same time we should keep in mind another directive of the Standard: the distance between the last rib and the stiffle should not disturb the movement of the dog. The point of buttock should be visible and well-distinguished. So we need to form a smooth and long line on the posterior part of the gaskins, descending a lot towards the hocks. The line should start from the point of buttock; - in case it is not well-distinguished, some extra hair will be of avail. Just above the point it is good to clear up up to the root of the tail in order to highlight the point of buttock even more.In case the hocks are high we can comb the hair backwards and make the shape of the hocks only using hair. We have to be careful not to miss the line going precisely through the hock, or else a rupture will be produced and the defect will be revealed. It is advisable to form round shapes of small columns from the hocks down to the paws so that the paws may look compact and integrated into the column (similarly to the front paws). The angulation should be formed from the hair on the front part of the gaskin; it should be well curved, sloping, about the same level with the hock (the rear angulation is correct if the imaginary line perpendicular to th ground goes through the point of buttock and the tiptoes). From here, we make a smooth line to the tuck up, the angulation of the stiffle remaining hidden by hair. I create this line using scissors, after having finished the transitions from the short zone to the long one with a sharp, long and wide tooth knife.Hindlimbs play a very important role in moving, as already mentioned, this is where the powerful propulsion comes from. Consequently, hindlimbs need to be muscular and strong. We can emphasize this feature by grooming but without thinning the hair on the gaskin. However, we shouldn’t leave too much hair, either, as if we wanted to tailor ”knickers” for the dog. This can be seen best from back view, and judges at the show will also examine the dog viewed from behind. As we well know, in motion hindlimbs are parallel, with hocks parallel with each other, with no deviation either in or out. Hereafter, this should be emphasized in grooming, as well.

From the base of tail to the outer part of the paws a smooth curve should be formed, as well as in the inner part, very similar to a bell. The proper distance between the hindlimbs viewed from behind is somewhat larger than the height of the hocks. Now we need to look at the dog again in its entirety as the lower line depends on the general aspect of the specimen. The chest should be deep, about the same level with the elbows, and the abdomen should not be hollow. Thus, beginning with the tuck up to the level of elbow I am going to form a straight line. However, a great care is needed with a robust dog – we should not leave too much hair on the abdomen zone or on the chest because they will become even more heavy; if, on the contrary, we deal with a specimen with fine bones and insufficiently deep chest, a light hair surplus might help. The transition from the ribs and the flanks to the chest with longer hairs should be done with great care to seem as natural as possible. The ribs are quite flat, the brisket is never barrel-shaped. Doing this part, I also use knives at the beginning, then I make corrections with scissors the way the hair grows (downwards direction). Too long hair left on the stern, though, might make the dog look short legged, or vice versa.

The tail represents an important element. It should be strong, set on high, with the base perpendicular to the right croup, and it should never be rolled on the back. So it is indicated to form a cylindrical tail, that is not too thick but not very thin, either. It should have hard, adherent hair, slightly rounded at the tip. Minor tricks can be applied as well; in case it is carried too much on the back, we might leave less hair on the back and more on the front side (where it is black), or inversely. This shape will be obtained after the hair has grown; first using a sharp knife, then the extra hairs hanging out from the cylindric form shall be cut with scissors.

By using minor or major grooming tricks we are looking for harmony and balance. Full grooming takes at least 3 or 5 hours, plus the maintenance of the fur between the three big stages of work. The hair thus obtained for the show will last longer by applying the rolling-coat-method.

O-Sense

O-Sense